First, some background. Greg Mankiw, who is one of the clearest economic writers there is, penned an essay “Defending the 1%.” He wasn’t looking to earn any friends but he was looking to frame the inequality debate. And on page one what do we read?

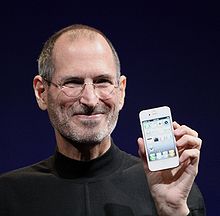

Then, one day, this egalitarian utopia [where everyone has the same wealth] is disturbed by an entrepreneur with an idea for a new product. Think of the entrepreneur as Steve Jobs as he develops the iPod, J.K. Rowling as she writes her Harry Potter books, or Steven Spielberg as he directs his blockbuster movies. When the entrepreneur’s product is introduced, everyone in society wants to buy it. They each part with, say, $100. The transaction is a voluntary exchange, so it must make both the buyer and the seller better off. But because there are many buyers and only one seller, the distribution of economic well-being is now vastly unequal. The new product makes the entrepreneur much richer than everyone else.

He goes on:

A well-functioning economy needs the correct allocation of talent. The last thing we need is for the next Steve Jobs to forgo Silicon Valley in order to join the high-frequency traders on Wall Street. That is, we shouldn’t be concerned about the next Steve Jobs striking it rich, but we want to make sure he strikes it rich in a socially productive way.

This is an old story. If you invent something that people like, you will earn profits. If you earn profits, you will likely have higher wealth than other people. That is the positive statement. The normative one is: do you want to take those profits away to equalize wealth again? Now there are many more steps to: do you really want to take Steve Jobs’ wealth away being the logical conclusion here but what Mankiw is doing is tapping into a common debating technique: people like Steve Jobs, people think he did good, therefore, we should think hard about taking stuff away from him. That device, useful though it is for grounding students, is very distracting in this context.

It was so distracting that Paul Krugman tried to take it on directly.

To see what I’m talking about, consider the differences between the iconic companies of two different eras: General Motors in the 1950s and 1960s, and Apple today.

Obviously, G.M. in its heyday had a lot of market power. Nonetheless, the company’s value came largely from its productive capacity: it owned hundreds of factories and employed around 1 percent of the total nonfarm work force.

Apple, by contrast, seems barely tethered to the material world. Depending on the vagaries of its stock price, it’s either the highest-valued or the second-highest-valued company in America, but it employs less than 0.05 percent of our workers. To some extent, that’s because it has outsourced almost all its production overseas. But the truth is that the Chinese aren’t making that much money from Apple sales either. To a large extent, the price you pay for an iWhatever is disconnected from the cost of producing the gadget. Apple simply charges what the traffic will bear, and given the strength of its market position, the traffic will bear a lot.

Again, I’m not making a moral judgment here. You can argue that Apple earned its special position — although I’m not sure how many would make a similar claim for Microsoft, which made huge profits for many years, let alone for the financial industry, which is also marked by a lot of what look like monopoly rents, and these days accounts for roughly 30 percent of total corporate profits. Anyway, whether corporations deserve their privileged status or not, the economy is affected, and not in a good way, when profits increasingly reflect market power rather than production.

Krugman, focussing on Apple but the subtext is Steve Jobs, argues that those returns were due to the presence of monopoly rents. Actually, not just monopoly rents but the exercise of monopoly power reducing investment. But the point is clear: yes, Steve Jobs should have had his wealth taken away in the sense that he shouldn’t have been able to earn monopoly rents for Apple’s inventions.

My contention here is that Steve Jobs is an incredibly poor example for the inequality debate. And in so many ways it is hard to know where to start.

So let me start with where the wealth came from. Apple has apparently sold 100 million iPhones in the US. Now to the extend that there were monopoly rents being earned here they came from the higher end, larger capacity, newer iPhones. My guess is that we are looking at the top quintile of the US income distribution. Now that is more than the 1 percent but from this perspective the transfer of wealth that was the result of the iPhone was from rich people to other rich people (ie., Apple shareholders). [I’ve made this argument before with respect to claims by Larry Summers]. So if we taxed these profits, then the chief beneficiaries would be other rich people: in particular, the rich people who consumed rather than invested in something innovative. I don’t care how you feel about inequality, that doesn’t seem like a good outcome.

But it goes further. There are few innovations where the entrepreneurs appropriates a large fraction of the social surplus generated by their efforts. Steve Jobs was certainly no exception. Indeed, the story of Steve Jobs is the story of industry transformation. An innovation leading to what is most appropriately termed imitation that leads to a dissipation of monopoly rents. In the case of the iPhone, that dissipation gave another quintile or two in the income distribution, smart phones in the space of just five years! Now some of that still went to Apple shareholders but compared with the counterfactual whereby that imitation did not occur, they earned less and what is more it is far from clear that inequality still was higher pre-iPhone than post-iPhone. So Krugman’s monopoly argument is weakened here.

This also hits at Mankiw’s argument too. For inequality to be justified, Steve Jobs and Apple shareholders have to hang on to their acquired wealth. But if what they did was only get a fraction of it but, in the process, dissipated the shareholders of competing phone manufacturers to consumer surplus, then inequality in the aggregate has fallen rather than risen. The question then becomes: would this have been better achieved by a tax on all rich people than the market process that generated this outcome? At the very least, that is how the question should be framed but by using Steve Jobs’ name in vain, we miss out on a proper analysis; an actual economic question rather than the political philosophy that we ended up getting.

It is even worse, by the way, if we use Mankiw’s thought experiment. If we start from the world where everyone has equal wealth and imagine the iPhone we are already in a mess of contradiction as the iPhone like so many similar products, serve the rich first. Instead, the better example would be Google. That is a product that one could imagine being invented in a world of equal wealth because it is free. But then of course, we have to explain advertising and we are back in trouble.

Finally, the problem with Steve Jobs is that he appears to be have been pretty unmotivated by wealth. The notion that his alternative option was a Wall Street trader seems implausible (and also impossible if we start from the thought experiment of equal wealth). Jobs, in fact, earned most of his money from Pixar and also after his death — in other words, it went to his family. As I argued elsewhere this, itself, muddies the whole debate as well.

In summary, Steve Jobs is an emotive example for the inequality debate and not at all a useful one. There are so many others. Please, everyone, let’s move this debate onto something more careful and real.

I agree with most of what you’re saying. But I’m confused by claim that Apple received monopoly rents. The better analogy I’ve seen is the fashion industry. Apple’s high prices are due to its appeal as a trendy, “in” product.

Apple’s use of patents to protect their products might argue that they are getting a premium, but the reality is that there have always been alternatives to Apple products. It’s unclear that Apple’s patents have allowed their high prices and profits as opposed to their popularity as the trendy product.

I’m a Krugman groupie, but also an Apple groupie and I have 20 percent of my portfolio in Apple (which is probably a bad idea). One note about Jobs: he *hated* Wall Street. I think he would have preferred Apple not even go public. He was not doing what he was doing for money, he was motivated by a love of creation. Dean Baker gives the example of Van Gough, whose works have hundreds of millions of market value, yet he lived in poverty.

I happen to live in Korea. I”m 95 percent sure Samsung ripped off Apple, though Apple also used Samsung chips so it’s a two way street there.

I think Krugman’s point about market position is justified, but if you’re talking about rents the real people earning money on rents is BIG PHARMA.

They are the largest lobby in the USA, more than the defense industry and oil. Their patents are often drugs that are just minor deviations from previous iterations and they charge insane prices and buy doctors, sending them on junkets.

Patents, btw, used to be 15 years. Now they’re 95 years for some products. Insane.

Of course, maybe we should ask how Apple even got started. Initially, Apple was in the buisness of selling devises that would allow people to get free long distance service. Back in the 1970s, some people noticed that if you took a whistle which was found in a box of Captain Crunch, you could blow it into a telephone and get free long distance phone calls. That is, the phone responded to certain frequencies. Jobs and company formalized this discovery by making a device which would send those frequencies over your phone line.

Then there was the Macintosh. Many of the elements which made the Mac a Mac were actually developed by Xerox. Jobs just appropriated Xerox’s technolology. Of course, if he tried that today, he would be sued for copyright and patent infringement.

So, another way of looking at it is that Steve Job’s phenomenal wealth came from engaging in illegal activities.

Then there is Bill Gates, and how he sold IBM and operating system he did not even develop and own. Moreover, DOS was basically a ripoff of CPM.

Which just goes to show that Republicans are big believers in fraud and theft…

“So if we taxed these profits, then the chief beneficiaries would be other rich people:” what? If we tax Apple profits which are due to rich people’s spending, the taxes don’t go back to the rich people that bought the iPhones (and taxes certainly don’t lower the price of the phones), the taxes collected can be used for things that everyone uses like schools or roads. Or to do even more redistribution, fund food stamps and unemployment insurance.

This is the same idea as a financial transactions tax. This would only affect the rich that do these transactions (and taking funds from the rich that collect fees — rents — on the transactions), but the funds generated could be used for the greater good. With the added benefit that it discourages excessive trading.

+1 to this.

Seconding Tom in MN: I also didn’t get why “if we taxed these profits, then the chief beneficiaries would be other rich people:” Is there an assumption that taxes on the “other rich” would be reduced to offset an increase in taxes on “monopoly rents” from higher end iPhones?